Having been a railroad telegrapher in my past life, I have a small collection of telegraph instruments which I will show on this page.

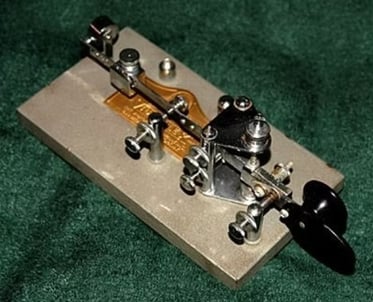

This is my original Vibroplex bug from 1939, SN 111779.

I have owned this bug since the early 60's so I suspect that I am its second owner. I was working for the GTW RR in Michigan and purchased this from an old time railroad telegrapher.

That funny looking plug on the end of the cord was inserted into the slide switch of a straight key so that the semi-automatic bug could be used. There is a shorting bar on this bug on the far side that you can't see.

On land-line telegraph you must always close the circuit with the shorting bar, otherwise no one can send anything if you leave it open.

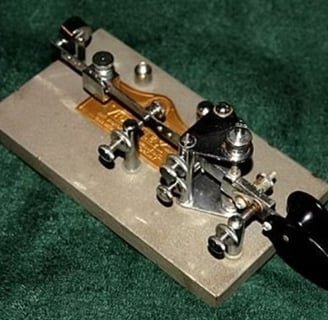

This is a Vibroplex bug with it's carrying case. This one has SN 127436 and is from 1944.

The leather handle on the case is broken which shows that this was used a lot in its day.

On this one you can see the shorting bar slide switch in the foreground. As mentioned above, another person could not send a signal on a landline unless you remembered to close your shorting switch.

This bug has serial number 378007 and is from 1975.

Notice that this one has a grey finish, instead of the more common black wrinkle finish. I am missing a couple of parts for this bug but most parts are still available from Vibroplex.

This is a Vibroplex Lightning Bug from 1976. The serial number is 381599.

This bug is new and in its original box. This model has a chrome base and it drives me nuts keeping the finger prints off of it when I handle it.....so I try not to handle it!

I keep this one wrapped in plastic in its box and take it out for show and tell when friends are over.

This spark proof key is made by Brelco, NY, model CAQZ-26026.

There is also some other numbers on the face plate. One that is a permanant part of the plate is NXsr-60008 and the serial number is stamped on the plate as 4464.

These keys were used in environments where "sparks" could ignite fumes from flamable, or combustable, material. The key contacts are totally enclosed in that box and sealed from the elements. Not only does this prevent sparks, but it also provides a salt-free atmosphere aboard ships to prevent corrosion of the contacts.

Here is an unusual straight key with a marble base.